ASEAN leaders are betting on TVET to power a green and digital future. The challenge is turning ambition into action.

By Shannon Kobran

Last week, I joined more than 1,500 delegates in Kuala Lumpur for the ASEAN TVET Conference, held under Malaysia’s ASEAN Chairmanship and the ASEAN Year of Skills 2025. The conference brought together policymakers, educators, and development partners to discuss the future of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in the region, and highlighted a clear recognition that the transition to greener economies cannot happen without skilled workers. TVET sits at the heart of this transformation.

What struck me most was the seriousness with which policymakers and practitioners discussed skills training—not as a secondary option to academic study, but as central to the region’s sustainable future. In his opening remarks, Malaysia’s Minister of Human Resources Steven Sim Chee Keong declared that “skills training will be the currency of our time.” Later, Deputy Prime Minister Dato’ Seri Dr. Ahmad Zahid bin Hamidi echoed this point: “Skills are the currency of the future, and TVET is the mint in which they are forged.”

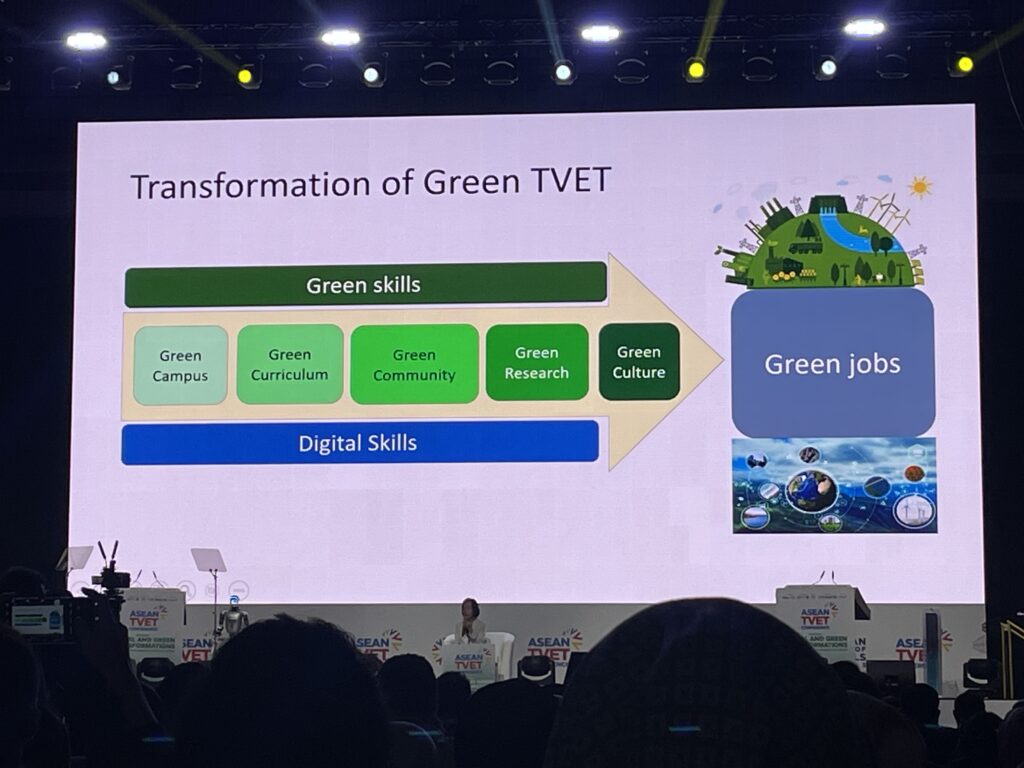

The vision of TVET as an economic engine was reinforced throughout the day: ASEAN-wide standards for green financing, talk of transnational TVET credentials, a proposed ASEAN Green and Digital Skills Task Force, and the creation of new centers of excellence. Regional collaboration was the refrain, yet the question remains: Will ASEAN be able to translate these frameworks into reality?

When it came to the substance of “green skills,” I noticed a curious imbalance. Panelists acknowledged that green skills are more than technical or digital proficiencies, yet again and again the emphasis returned to AI, data, and cybersecurity. Certainly, these are vital. But, as several speakers noted, technology changes faster than curricula. To focus only on today’s tools risks training students for jobs that may vanish tomorrow. What lasts are capacities like agility, resilience, and an attitude that values lifelong learning. As I’ve said before, embedding education for sustainable development, critical thinking, and socio-emotional learning—so-called “soft skills,” or human skills—alongside technical training will be essential if ASEAN wants to prepare a workforce not just for the green economy, but for a sustainable society.

Dr. Siripan Choomnoom, President of Institute of Vocational Education Bangkok Council Office of Vocational Education Commission (OVEC), presents Thailand’s approach to TVET.

Dato’ Dr. Hamidi provided some intriguing statistics: more than half of Malaysian school leavers now choose TVET, and TVET graduates report 91% employability. On paper, this is an extraordinary success. And yet Malaysia’s recent Voluntary National Review suggests a different story: the country continues to struggle with employment-related SDG indicators, and many young people prefer informal jobs in gig work or content creation to the formal labor market. The numbers also don’t fully capture social perceptions of vocational work: many parents would rather see their students pursue a university degree, even if the job prospects for TVET graduates are better. Until TVET is seen as equal in prestige to university—and until the jobs it leads to are attractive to students—the narrative of success will remain incomplete.

Other ASEAN countries are tackling this head-on. Nur Hygiawati Rahayu, Director of Manpower at the Indonesian Ministry of National Development Planning, for example, shared the country’s “Golden Vision 2024,” which highlights the green economy as a pillar of national development. Crucially, Indonesia has adopted an operational definition of “green jobs” and a system for measuring them—a step beyond the vague rhetoric I heard from other countries. Dr. Akiko Sakamoto from the International Labour Organization’s Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific similarly stressed that green transitions must be just transitions, rooted in inclusivity, social protection, and transferable skills. These are important reminders that sustainable solutions are not only technical, but also social.

Industry case studies gave the discussions practical grounding for championing effective TVET strategies. Mr. Ahmad Munir Akram Ahmad Faiz from PETRONAS, Malaysia’s state energy company, explained how the company runs aims to raise the visibility of TVET by reaching out to secondary schools at the point when students must decide whether to pursue an academic or vocational track. He also explained how PETRONAS is embedding sustainable practices in its vocational training programs, reusing surplus materials from its suppliers for trainee welders, fitters, etc. Still, Munir admitted, “We all have our day jobs.” For TVET initiatives to scale, they cannot rely on the enthusiasm of individual employees or ad hoc corporate goodwill.

Globally, ASEAN’s debates echo a wider conversation. Around the world, countries are grappling with the pressures of AI, the urgent demand for skilled workers in renewable energy and other green sectors, and young people’s frustration at finding decent, stable jobs. Singapore, with its SkillsFuture initiative and prominent polytechnics, is often cited as a leading example in the region because it creates a culture of lifelong learning through credits, employer partnerships, and flexible pathways. The principle—that education does not end with a diploma—is one the rest of ASEAN would do well to take to heart.

My final observation is about language. Over the course of the day, I noticed that while “green” and “digital” were repeated endlessly, the Sustainable Development Goals were hardly mentioned. With the exception of one presentation from Associate Professor Dr. Mustahafah Mohd Tahir from Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka, who spoke about embedding SDG awareness in curricula, the agenda was largely silent on the SDGs as a global framework. For years, the SDGs have provided a common vocabulary for sustainable development. As we approach the 2030 deadline with only 17% achieved, is this a signal that we are moving away from them as a shared language of global development? Or are we simply failing to integrate them into TVET policy discourse? Either way, it leaves me wondering whether we risk losing a universal language just when cooperation is most needed.

The ASEAN TVET Conference offered energy, ambition, and a strong chorus of voices calling for collaboration. But the hard work now begins. If skills are truly to be the currency of the future, ASEAN must ensure that the “mint”—its TVET systems—produce not only employable graduates, but adaptable, resilient citizens prepared for a changing world.

The author and SDG Academy Education Intern Wendy Zhou at the Conference.

Shannon Kobran is the Head of Education and Training at the SDG Academy.